‘Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.’ Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt, and remained there until the death of Herod. Matthew 2:13-15

In these early days of the new year, the Christmas story gives way to the darker remembrance of the murderous jealousy of King Herod and the Holy Family’s flight into Egypt. So soon after the glory and wonder of the nativity, Jesus, Mary and Joseph are fleeing for their lives. And in doing so they share in the brutal experience of millions of refugees down through the ages and in our own time.

One of the key priorities of the Anglican Alliance is responding to the most vulnerable, in particular refugees and migrants. The Anglican Alliance serves to connect and equip the worldwide Anglican family to welcome and support displaced people and to raise their rights.

Joel Kelling is the Anglican Alliance’s Middle East facilitator. Last year he moved to Jordan, a country that hosts over a million refugees from the wider region. Here, Joel describes a week he spent amongst refugees in different parts of Jordan and reflects on the diversity of people, stories, and experiences behind the catch-all label. He shares questions he faced along the way and finds inspiring stories of faith and hope in challenging environments. If you would like to support the work described here, please see details at the end. Here is Joel’s reflection:

In the City

The week began as usual with a taxi ride through the busy downtown streets of Amman up to St Paul’s Anglican Church in Ashrafiyeh. Ashrafiyeh is perched on a steep hillside and is Amman’s highest point, with views over the rest of the city. It is a neighbourhood that has seen many displaced people come and go over the past century.

St Paul’s Church was itself founded by Palestinian refugees in the 1950s. What began as a small house church has flourished into a vibrant and diverse congregation, with a building in the traditional style of Anglican churches in the region. What hasn’t changed is the welcoming nature of the church as a community. In the decades since it was established St Paul’s has become home to new generations of refugees, most recently from Syria and now Iraq. The church is led by Fr. George al-Kopti. He and his wife Mary have cultivated ministries for women and youth but don’t make any distinction between refugee and local, celebrating the value of each individual.

Elias and Dunya*

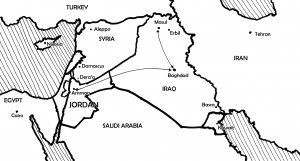

Unlike a normal Sunday, at the end of the service Fr. George and I walk down the hill a short way from the church to pay a visit to Iraqi members of the congregation – Elias and Dunya, and their daughter Linda. As we sit, Dunya brings us cups of coffee and Elias begins to tell us their story. It is a story of faith and resilience, beginning when they fled from Mosul in 2014. Informed by neighbours that ISIS / Da’esh was closing in on the city, the family fled to Baghdad. There Elias joined a church, working as a caretaker. But they were still not safe. One of Elias’s colleagues was kidnapped and Elias received death threats on account of his faith. After men Elias believed to be the kidnappers paid a visit to the family home, seemingly to scope it out, the family fled, leaving almost everything they had behind to seek a place of greater safety.

This story is, sadly, not unique. Today there are 66,971 registered Iraqi refugees in Jordan [1], with an estimated additional 80,000 unregistered Iraqis residing within the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Christians from Iraq feel especially vulnerable. Christians are believed to comprise a significantly higher proportion of Iraqi refugees than in the population in Iraq [2] and Fr. George tells me that members of his congregation complain to him from time to time that, as Christians, they feel discriminated against by local UN staff. They talk of promised visits not materialising and years spent waiting for papers, whilst families from other backgrounds receive theirs within months. In addition, Iraqis – unlike Syrians – are not able to work in Jordan legally, further increasing their vulnerability and reliance on assistance.

Fr. George has arranged food coupon distributions as well as finding other ways to support the families he knows in Ashrafiyeh, but he is stuck when it comes to helping Elias and Dunya. Their daughter Linda has severe mental and physical difficulties and requires regular medication. They receive support from the UNHCR, which covers some of Linda’s medical bills, but it is not enough. Fr. George tells me that her parents are unable to sleep at the same time, in order to make sure she is properly cared for. Elias shows me Linda’s recent prescriptions and says that he has heard that there are neurological treatments available in Israel and Egypt, but that they have no way of affording it. They want to know if I can help, but I feel that all I can do is tell their story, which doesn’t feel like enough. Fr. George says that he doesn’t want to assist the Christian depopulation of the Middle East, but in this case the family would perhaps be better off abroad. I can’t promise anything, and don’t, but tell them I’ll see if there is anyone who might be better placed to help.

Travelling North

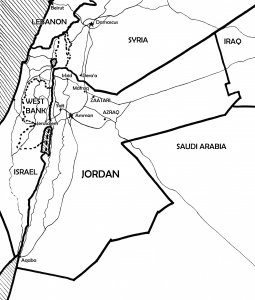

Over the next few days, I have the opportunity to visit the Zaatari and Azraq refugee camps in the north of Jordan. These two cities of displaced people (with populations of 78,554 and 58,000 respectively) are the iconic image of refugee life the world over, yet fewer than 1 in 5 [3] of registered refugees in Jordan live in camps. The vast majority, like Elias, Dunya and Linda, are in rented homes in urban areas.

My purpose in visiting the camps was to see the work of the Holy Land Institute for the Deaf (HLID). The organisation is a ministry of the Diocese of Jerusalem and runs a school for deaf pupils in Salt, Jordan, as well as rehabilitation centres in two sites in the Jordan Valley. HLID began working in Zaatari in 2012 and in Azraq much more recently, in 2017, working in partnership with other Jordanian disability organisations.

Zaatari

I travelled first to the Zaatari camp on the main road to Baghdad. It feels vast, the scale of the camp overwhelming. Sabri Shanteer, HLID’s head of outreach, takes me to a high point in the centre of the camp and in every direction I can see row after row of ‘caravans’ (there are no tents here) – the metal homes with extensions made out of tarpaulin and corrugated sheeting. The caravans densely line the narrow and wiggly roads in the western quarter of the camp, testament to its rapid development since it opened in 2012. The rest of the camp is more ordered, with streets laid out on an east-west grid. The population of Zaatari is currently 78,554 [4], down from a high of 83,000, but still dwarfing the neighbouring village of Zaatari, from which it derives its name, and Mafraq (home to around 58,000 residents). It is theoretically possible to find work in both Zaatari and Mafraq – and to work legally (36,000 work permits were given to Syrian refugees in 2017). Jordanian police at the entrance tell me that it is easy to get permission to leave the camp for up to three weeks at a time.

I travelled first to the Zaatari camp on the main road to Baghdad. It feels vast, the scale of the camp overwhelming. Sabri Shanteer, HLID’s head of outreach, takes me to a high point in the centre of the camp and in every direction I can see row after row of ‘caravans’ (there are no tents here) – the metal homes with extensions made out of tarpaulin and corrugated sheeting. The caravans densely line the narrow and wiggly roads in the western quarter of the camp, testament to its rapid development since it opened in 2012. The rest of the camp is more ordered, with streets laid out on an east-west grid. The population of Zaatari is currently 78,554 [4], down from a high of 83,000, but still dwarfing the neighbouring village of Zaatari, from which it derives its name, and Mafraq (home to around 58,000 residents). It is theoretically possible to find work in both Zaatari and Mafraq – and to work legally (36,000 work permits were given to Syrian refugees in 2017). Jordanian police at the entrance tell me that it is easy to get permission to leave the camp for up to three weeks at a time.

Azraq

Azraq is a completely contrast. On the road to the Saudi Arabian border, it is isolated and in the middle of desert, 30km from the town with which it shares its name. The camp is made up of five ‘villages’ spread out from one another, with desert between. The total population of the camp is officially 41,089, though HLID staff quote a lower figure of 35,000, which tallies with some NGO estimates. HLID’s Azraq coordinator tells me she thinks it is a much better place than Zaatari, based on the neat rows of caravans, aligned one to the next, with an orderliness which is lacking in Zaatari. I’m not sure that I can agree – the regimented quality in such hot and deserted surroundings lends it the air of a prison, which at least one of the villages effectively is, home to political refugees whose status has yet to be determined by the Jordan security forces, meaning they are unable to access the rest of the camp, let alone leave. When I ask Mr. Shanteer why Azraq is located where it is, he says that security and control are big factors, with lessons learned from previous challenges at Zaatari, which is both closer to urban population centres and the Syrian border.

I’m not sure whether the camps are what I expected or not. They are large and feel permanent, which is unsurprising given their age. The camps both have bus networks and bicycles that can be hired to get around them. Non-Governmental Organisations (including Oxfam, Mercy Corps and the Norwegian Refugee Council) have provided football pitches and built schools, and there are hospitals and cemeteries. Despite the fall in population in Zaatari, a policeman tells me that 80-100 children are born in the camp each week. There are markets and mosques too (though no churches; it seems there are no Christians in the refugee camps here5), which give a semblance of normality. However, the reality remains that the situation is not normal. Thousands of Syrians are here, miles from their homes, and often separated from family members.

That is why HLID has a presence in both camps, in order to provide care and support that would otherwise be absent. And whilst these descriptions of the camps may be bleak, I’m seeking to tell a story of hope amid exile.

In both camps HLID are engaging with children with a number of challenges, from blindness and deafness to problems with motor skills and learning difficulties. In port-a-cabins arranged neatly around small well-tended gardens, 50 children in Zaatari and another 30 in Azraq are receiving education in language learning, personal health and hygiene and creative arts.

Farah, who is a part of HLID’s outreach team, tells me that there is no official Syrian sign-language, and that typically the deaf students have not been able to communicate with each other or their families until now. HLID volunteers are teaching not only the students but also their parents how to communicate through Jordanian sign language. Their worlds are opening up.

Remarkably, all but one of the volunteers are Syrian refugees themselves, resident in the camp. None of them had any prior knowledge of sign language or working with special educational needs children. HLID has invested in teaching them and I’m moved by their dedication to the cause. The only teacher who isn’t a refugee is Marwan, who comes from Mafraq, and is a graduate of HLID. He himself is deaf and seeing him teaching deaf children, not only Arabic but English as well, is inspiring.

Finding Hope

I speak with one of the volunteers in Zaatari, whose name – Amal – means ‘hope’ in Arabic. She tells me how she feels her life has been enriched by the experience of working with HLID and imagines a time when HLID are able to open institutions in Syria. She tells me of her hope to return home and to continue working with them. It’s good to hear her tacit optimism and desire to return home, and her dream not only of rebuilding but also of developing new opportunities for more inclusivity within Syrian society in the future.

As I visit different classes in Zaatari and Azraq, the signs of summer camp are everywhere. There are dioramas and models for educational use, including on road safety, a model of the Kabaa in Mecca and a wool clad model sheep used during Eid. The most heart-breaking model is one made by the students themselves of a boat, filled with action figures and dolls, which Farah explains to me represents the boats in which refugees have attempted to reach Europe. In the midst of their own daily challenges, these children are remembering other displaced people fleeing harm and seeking safety at incredible risk to their lives.

In Azraq, I see teachers using a wonderfully hand-crafted book, which they use as a pre-Braille learning device, sensitising young hands to the feel of shapes and textures. Mr. Shanteer explains that they also have two Braille machines at the camp but would like to have more in order to engage with more children at the same time. He has already explained that with more funding they would be able to reach children in the camps that they are currently unable to help. They need more teachers as well as more classroom space and materials and he wishes he could pay the volunteers more than the ‘pocket money’ they receive currently. I let him know that it is my hope that this piece can alert donors to the opportunities as well as the incredible work that HLID is doing.

Returning home

I return to Amman (aware at the checkpoint as I leave that it is so simple for me) tired from the heat and the emotional engagement but inspired and encouraged by the remarkable work of HLID. For all the difficulties of life in a refugee camp, the structure and support networks in general, and those offered by HLID in particular, are good. If they had more funding they could support more children and parents who would benefit from the rehabilitation and educational programmes.

I’m not sure the same can be said for the urban refugees, especially those who are not registered with UNHCR, and particularly for the Iraqis who have to choose between working illegally and using up whatever savings they have and relying on handouts. There is a widespread and persistent myth in Jordan that Iraqis are wealthy and that they will be fine. The Syrian civil war is ghastly and will leave deep scars, but the Syrians I have met do talk about returning home one day. The same cannot be said for the Christian Iraqis I have spoken with, who describe a social contract having been broken; intolerance towards Christians and other minorities doesn’t exist solely within the ranks of Da’esh. For Elias and Dunya, a return is unthinkable.

What’s next?

Fr. George and I contemplate the need for sustainable long-term solutions, supporting host communities as well as refugees. We continue a conversation about the establishment of a clinic on the premises of St. Paul’s, an idea he has had for some time. Soon afterwards, we began discussions with an NGO about their potential support and assistance, and the need for a strategy for how the Anglican Church responds to these crises of displacement. Now, a few months on, the dream has become reality and the fledgling clinic has begun (see story here).

Throughout this time I’ve been struck by the way we use language around the people affected by conflict and displacement. The teachers and pupils in Zaatari and Azraq are refugees, but this doesn’t begin to describe the fullness of who they are. Fr. George refuses to refer to ‘refugee ministry’ and instead talks about the activities of the parish, despite approximately half of it being made up of refugees. In part this is because the Anglican Church in Jordan itself consists largely of the descendants of Palestinian refugees and in part because of the strength of hospitality inherent in Arabic culture. But a greater part, I believe, is born out of faith and the belief we are all made in the image and likeness of God and equally loved by God. This must inform how we engage with all around us.

If you would like to support the work of the Holy Land Institute for the Deaf (HLID) or the work of St Paul’s Church, you can find details of how to donate here: HLID and St Paul’s. Each also has a Facebook page: HLID Facebook and St Paul’s Facebook.

* Names have been changed to protect the identities of those referenced.

1 UNHCR – Registered Iraqis in Jordan, 15th August 2018.

2 Christians are believed to make up more than 10% of the Iraqi refugee population in Jordan, despite comprising only 3-5% of the population in Iraq. However, it’s difficult to know the true numbers as the UNHCR does not publish religious identity figures.

3 UNHCR – Registered Persons of Concern Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Jordan

4 ibid

5 Anecdotally, Christians have described feeling unsafe in the refugee camp environments, preferring to join urban communities and local Christian congregations, as is the case in Ashrafiyeh.